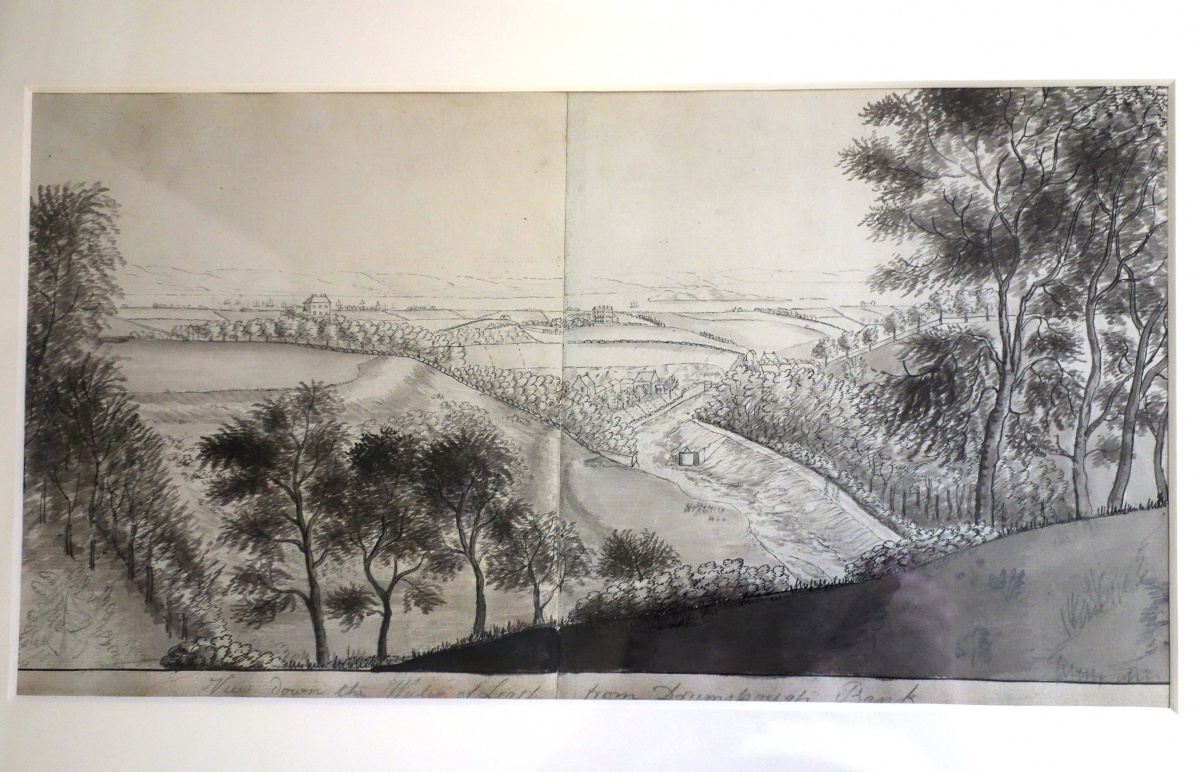

The lost view of the Water of Leith

Lord Cockburn’s view rediscovered!

In Memorials of his Time, that great book about early nineteenth-century Edinburgh and its citizens, Lord Cockburn remembered fondly the view that had recently been destroyed when the Earl of Moray developed his land to the west of the first New Town.

‘It was then an open field of as green turf as Scotland could boast of, with a few respectable trees on the flat, and thickly wooded on the bank along the Water of Leith. Moray Place and Ainslie Place stand there now. It was the beginning of a sad change, as we then felt. That well-kept and almost evergreen field was the most beautiful piece of ground in immediate connection with the town, and led the eye agreeably over to our northern scenery. How glorious the prospect, on a summer evening, from Queen Street! We had got into the habit of believing that the mere charm of the ground to us would keep it sacred, and were inclined to cling to our conviction even after we saw the foundations digging. We then thought with despair of our lost verdure, our banished peacefulness, our gorgeous sunsets… I have stood in Queen Street, or the opening at the north-west corner of Charlotte Square, and listened to the ceaseless rural corn-craiks, nestling happily in the dewy grass’.

Fortunately we can see once more Lord Cockburn’s woody banks leading down to the Water of Leith and the northern scenery beyond. A drawing made when the future judge was about ten years old has been rediscovered which is the earliest view of the land north from Drumsheugh bank and provides unique visual information on the buildings and plantings which then surrounded the Water of Leith. The draughtsman was the Anglo-swiss antiquary Francis Grose. Preparing material for his great work The Antiquities of Scotland he criss-crossed Scotland over a three year period from 1788 to 1790. He was certainly in Edinburgh in September 1788, again in May and August the following year and back once more in May 1790. The rediscovered view could have been drawn in any of those months, but not later; as by the end of 1790 Grose had completed his Scottish research as is not known to have returned.

Fortunately we can see once more Lord Cockburn’s woody banks leading down to the Water of Leith and the northern scenery beyond. A drawing made when the future judge was about ten years old has been rediscovered which is the earliest view of the land north from Drumsheugh bank and provides unique visual information on the buildings and plantings which then surrounded the Water of Leith. The draughtsman was the Anglo-swiss antiquary Francis Grose. Preparing material for his great work The Antiquities of Scotland he criss-crossed Scotland over a three year period from 1788 to 1790. He was certainly in Edinburgh in September 1788, again in May and August the following year and back once more in May 1790. The rediscovered view could have been drawn in any of those months, but not later; as by the end of 1790 Grose had completed his Scottish research as is not known to have returned.

A good reason for believing that the drawing dates from 1788 or very shortly after is that in 1788 Lord Gardenstone commissioned the artist Alexander Nasmyth to create the circular Roman temple, which of course survives, on the site of the earlier well house. Grose’s drawing clearly shows the 1760 well house and not Nasmyth’s temple. It is quite possible that Grose knew Nasmyth. They had friends in common, not least Robert Burns who wrote Tam o’ Shanter for Grose. Another mutual friend was Robert Riddell of Friars Carse in Nithsdale. Riddell was a fellow antiquary and Grose’s travelling companion on many of his Scottish and, in particular, Edinburgh journeys. Grose was not an elegant or fanciful draughtsman. He was concerned in recording exactly what he saw. What he saw when he peered over Drumsheugh bank he recorded faithfully. And that makes his drawing the more precious.

by James Holloway