How Dean got its bridge

By David Perry

In autumn, 1825, John Learmonth, the senior partner in the family’s coach-building business, feued 133 acres of the Dean Estate from Sir John Nisbet. The southern boundary of this land stood on the edge of an abyss - the Dean - created by the Water of Leith as it cut its way through the rock over the centuries. 100 feet below, the river flow drove the mills of the Village of the Water of Leith. And 500 feet across the ravine, on Randolph Cliff, grand new buildings were going up in the New Town. Learmonth wished to build on his feued land. And so he and Nisbet approached James Jardine, Civil Engineer, to design a bridge to cross the Dean.

They did not know that earlier that year the Trustees of Cramond District had already employed Jardine to survey and design such a bridge. The road to Edinburgh from the north crossed the rickety Belford Bridge with its steep gradients, along Belford Road to Drumsheugh Toll, where dues were paid, causing hold-ups. The road then swung to the south, through the New Town and into old Edinburgh. The Trustees wanted a better road, and for it to be free of tolls.

Jardine produced a design which was approved by the Trustees and by Learmonth, who promised money in exchange for full public rights. But there was a difficulty. Previously, Learmonth had made an agreement with Nisbet that he would build "a handsome and sufficient bridge over the Water of Leith", to be designed and built by Gillespie Graham, architect.

So Jardine's design was submitted to Graham, who rejected them and produced his own. In April 1828 the Trustees consulted Thomas Telford and both Jardine’s and Graham’s plans were sent to him for vetting. Learmonth muddied the waters further by writing to Telford saying he should make his own design if he was not happy with those sent to him. At this point Telford withdrew from the project, and sent all the paperwork back to Edinburgh, not wishing to have anything more to do with it.

Telford was prevailed upon by all parties to change his mind. He produced his own design in May 1829, which was accepted. John Gibb and Son of Aberdeen were appointed contractors. Telford had used them before in the improvements on Aberdeen Harbour. Charles Atherton was appointed Inspector of Works. Learmonth provided the finance. And so, in July 1829, four years after the original proposal, work could begin.

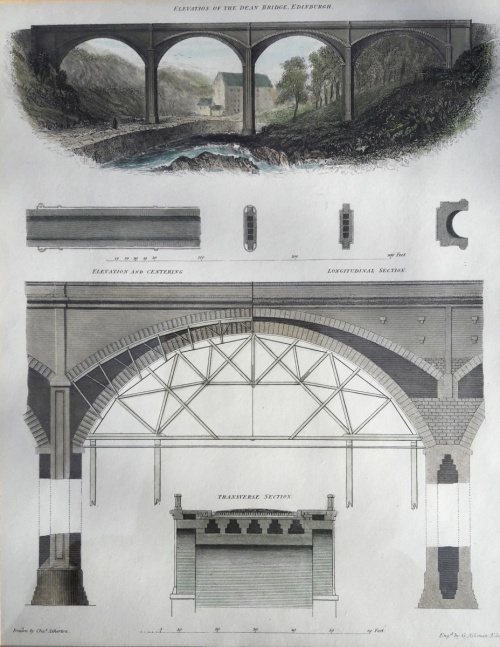

The bridge as originally designed was 106 feet high, crossing the 450-foot ravine with three arches. Work started on the foundations, but a problem was immediately encountered. The rock on the south (city) side was crumbling and insecure. So the bridge had to be redesigned to be wider, now with four arches, and the southern foundations could now be secured on solid rock.

The wooden scaffolding erected for the building of the bridge was itself a work of art. People came from long distances to see the bridge going up. There was a special skill involved in the centering of the arches. The piers and arches were hollow, and this allowed each block to be bedded accurately as it could now be viewed from both sides. Hand-operated cranes were used to lift the stones into place. (The hole in each stone made for the claw grab can be still be seen.) The hollow design was safer than a solid construction, as the extra weight could cause a bridge to fail. A side benefit was that the bridge was less expensive to build. Allowances had to be made when the scaffolding was removed, as the arches had to settle evenly.

The wooden scaffolding erected for the building of the bridge was itself a work of art. People came from long distances to see the bridge going up. There was a special skill involved in the centering of the arches. The piers and arches were hollow, and this allowed each block to be bedded accurately as it could now be viewed from both sides. Hand-operated cranes were used to lift the stones into place. (The hole in each stone made for the claw grab can be still be seen.) The hollow design was safer than a solid construction, as the extra weight could cause a bridge to fail. A side benefit was that the bridge was less expensive to build. Allowances had to be made when the scaffolding was removed, as the arches had to settle evenly.

The bridge was completed in December 1831, well before the planned date. But the carriageway and pavements had not yet been laid out. These works were finally completed on 8th May 1832, the road was surfaced the next day and the bridge handed over to its owners.

One story often repeated is that John Gibb, having completed the project early, put gates either side of the bridge and charged a penny a time to cross it. As it was the wonder of the time, he would indeed have made a pretty penny. This particular hare may have been started by a correspondent to the Scotsman of 10th September 1929, relating this story told by his father, an Aberdonian, who was 32 at the time.

The cost was estimated at £18,566, largely borne by Learmonth, who now was Lord Provost of Edinburgh. And there was no cost at all in human lives. The Fathers of the City of Edinburgh looked on with interest, but took no part as the city boundary ended at Randolph Cliff.

Sadly for Learmonth, economic conditions in the building industry turned very bad in the 1830s and 1840s. He did get some of his investment recompensed by the Cramond Trustees. But it was twenty years before the first buildings went up in Clarendon Crescent. The real winner was the City of Edinburgh. All roads and bridges in the now extended borders became City property after the passing of the Roads and Bridges Act 1878.

And not a penny was paid for Dean Bridge.